Recent studies in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics have shed light on pathogenic mechanisms of the sexually-transmitted parasite Trichomonas vaginalis and the HIV-associated opportunistic lung fungus Aspergillus.

Fatty acid addition lets a parasite stick

Trichomonas vaginalis, commonly known as trich, is the most common curable sexually transmitted disease, and the vast majority of people with the disease – upwards of 70 percent – do not experience symptoms, according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. However, the protozoan parasite can increase an infected person’s risk of contracting HIV or developing cancer, and can cause preterm labor in pregnant women. In other parasites, a protein modification called palmitoylation, the addition of a 16-carbon saturated fatty acid to cysteine residues of a protein, regulates infectivity. In a new paper in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, researchers at the Instituto Tecnologico de Chascomus in Buenos Aires, and the University of California, Los Angeles, enriched palmitoylated proteins from T. vaginalis and found numerous palmitoylation sites in pathogenesis-related proteins. Yesica Nievas and colleagues report that disrupting palmitoylation reduced the protist’s self-aggregation and adhesion to host cells. This work establishes the importance of palmitoylation in T. vaginalis proteins for infection and suggests that palmitoylation enzyme inhibitors may help treat the infection. DOI: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000018

How a fungus outfoxes the macrophage

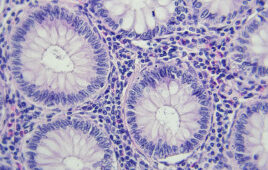

Aspergillus fumigatus is an opportunistic pathogen in the lung. People with compromised immune systems, either from disease or immune-suppression therapy, are especially vulnerable to the airborne mold spores, called conidia. In a healthy person, macrophages in the alveoli take up the fungus and normally an acidic organelle called the phagolysosome destroys it. Conidia from A. fumigatus, however, disrupt acidification of the phagolysosome and prevent the infected macrophage from committing suicide through apoptosis. Researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Germany investigated the immune evasion strategies the pathogen uses by infecting cultured macrophages with magnetically tagged Aspergillus conidia from a virulent strain or a less infectious mutant strain. Hella Schmidt and colleagues then extracted phagolysosomes from macrophages infected with each strain and compared their proteomes. In a paper in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, the team reported that the more virulent strain reduces maturation of the phagolysosome and proinflammatory immune signaling. These disruptions ensured that the more virulent strain had a comfortable place to survive inside the host. Doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000069.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics