A researcher’s decision to purify RNA or not depends on their unique application, despite having near-perfect RNA purification technologies at their fingertips.

|

RNA is one of the most important biomolecules in existence. For controlling myriad biological processes, RNA is second in command, with DNA being the master controller. By utilizing current technologies, researchers can pretty painstakingly purify RNA. But challenges remain such as keeping RNA stable. Depending on the research application, purification may, or may not, be necessary.

Susan Eshleman, MD, PhD, professor of pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md., directs a CLIA-certified HIV genotyping lab that is involved in the characterization of HIV viruses, detection of drug resistance mutations in HIV, and analysis of viral sequences. “The HIV virus has an RNA genome, so if you want to look at HIV sequences, almost every application requires that you first isolate the RNA from the sample,” says Eshleman. Sample types are often plasma or serum. Once HIV RNA is isolated from a sample, it must first be reverse-transcribed into cDNA; amplification of the cDNA pool by PCR, and sequencing of the amplified DNA typically follow.

In Eshleman’s case, the entire workflow from RNA isolation to HIV sequence interpretation is accomplished using one kit: the ViroSeq HIV Genotyping System, manufactured by Celera (Alameda, Calif.) and marketed by Abbott Molecular. “[The kit] is a complex system that includes all of the reagents needed to take a sample of plasma and produce a drug resistance report; it also includes the software used for analysis of the resulting HIV sequences,” says Eshleman. The kit can be used to isolate HIV RNA with minimal degradation, which is necessary to amplify the large (>1000-bp) HIV fragments needed for HIV genotyping.

Mingjun Huang, PhD, executive director of antiviral drug discovery, Achillion Pharmaceuticals, New Haven, Conn. has to isolate RNA, but not purify it, which probably saves some time. Huang and her colleagues developed a high throughput derivative of the Replicon assay that enables them to screen for potential inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication. The endpoint readout is a dot blot, which detects viral RNA that represents replication biomarkers.

In both of these cases, an RNA purification technology was used. And, luckily there are plenty of companies developing them.

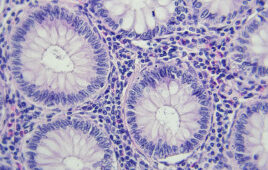

RNA: Fresh or aged

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.) has multiple RNA purification technologies for the isolation of total RNA, mRNA, or microRNA from fresh or archived tissue specimens. All of the technologies for isolation of total RNA, however, are based on the principle of silica-RNA binding in the presence of a chaotropic salt. The RNA input can be anything from bacterial cell, human tissue, plant tissue, etc. And, cell-based samples go through the basic bind-wash-elute workflow in which they are first lysed by the chaotropic salt. Ethanol-containing buffer is then added to that lysate, which is subsequently loaded onto a silica-based binding column that captures the RNA. A series of washes removes unbound material and cellular debris. Finally, the purified RNA is eluted from the column.

In contrast, the products for mRNA purification are based on the principle of capturing the polyadenylated tail on mRNA on an oligodT-derivatized bead. The input here can be either crude lysate or purified total RNA from which mRNA is to be isolated. “With these kits, you basically hybridize your mRNA, spin down to pellet the beads, remove everything that did not bind by doing a series of washes, and then elute off the purified mRNA,” says Steve Michalik, MA, genomics product manager at Sigma-Aldrich.

Invitrogen Dynal, a part of Life Technologies, Oslo, Norway, makes a slightly different RNA purification technology than Sigma-Aldrich: Dynabeads are a magnetic bead-based RNA isolation technology. “The Dynabeads technology has been on the market since 1986 and has been used in a lot of different applications and instruments—popular with the pharma/biotech industry,” says Haege Wetterhus, segment director of cellular & molecular research at Invitrogen.

The principle of binding to Dynabeads is hybridization. “The kinetics of this hybridization are very good, comparable to the kinetics of hybridizing in solution,” says Marie Bosnes, PhD, senior scientist of molecular applications, Invitrogen. “The beads float around and the risk of meeting something to hybridize to is increased because it is almost as if it is hybridizing in solution.”

The way it works? The magnetic bead is derivatized with oligodT, which can bind and capture the poly A tail of mRNA. The input? Anything from crude cell lysate to purified total RNA. “If you are looking for HIV virus, you can even put in serum or plasma because HIV virus has a polyadenylated RNA genome,” says Michael Muse, PhD, product manager of Dynabeads for mRNA isolation at Invitrogen. “So the input can be any liquid containing polyadenylated RNA.”

“An advantage for pharma and biotech is that they can use the oligodT beads for mRNA isolation with liquid handling robots in a high throughput format,” says Erlend Ragnhildstveit, PhD, research area manager, Molecular Separations, at Invitrogen. “Especially if you want to do real time qPCR, what is then an important factor is the cost per sample. Because you are running so many samples, the cost is a factor. With the Dynabeads oligodT, you can actually scale up and scale down. And this may be a deciding factor when it comes to high throughput platforms.”

According to Michalik, there are two big challenges with RNA purification. One of those challenges is eliminating genomic;DNA from RNA samples, especially those produced with the aim of amplification. “The only way to completely remove the DNA is by DNAse digestion,” says Michalik. Sigma-Aldrich produces kits for removing DNA from RNA samples. One kit, called AMPD1, contains a method and an RNAse-free DNAse for removing genomic DNA from RNA samples.

The other major challenge Michalik mentions is keeping RNA safe from destruction by cellular RNAses—robust enzymes that are very difficult to inactivate. These RNAses are found naturally in cells and tissues. So when an investigator wants to isolate RNA from an archived tissue sample that has not been protected against RNAses, for example, they can expect that any RNA isolated from that sample will likely be degraded. Sigma-Aldrich includes two RNAse-inactivating mechanisms in its RNA purification kits—a chaotropic salt, and the reducing agent beta-mercaptoethanol. Michalik recommends freezing tissues immediately after isolating them and/or storing them in RNAlater (a Sigma-Aldrich product) to protect against RNA degradation during long-term storage. “But if you snap-freeze tissues, it’s imperative that the cells are homogenized and disrupted immediately in the presence of chaotropes and a reducing agent prior to thawing, to ensure that you don’t degrade your RNA,” he says. “If you just throw the tissue in without homogenizing, you won’t disrupt the cells enough to allow the reducing agent and chaotrope to penetrate into the tissue and prevent the RNAse degradation from occurring.”

|

This article was published in Drug Discovery & Development magazine: Vol. 11, No. 12, December, 2008, p.26-28.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics