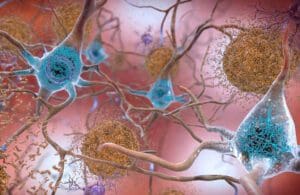

Beta-amyloid plaques and tau in the brain. [Image from National Institute of Aging]

The Estée Lauder family has donated $200 million to the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), a nonprofit they founded in 1998 to support Alzheimer’s research. The gift is the largest ADDF has received.

“We’ve deployed about $270 million so far for about 700 programs in 19 countries of drug discovery and development over the past 25 years,” said Dr. Howard Fillit, co-founder and chief science officer of the nonprofit.

The Lauder gift will sustain ADDF’s philanthropic model for the next 10 or 15 years, Fillit said. “We want to use our donors’ money solely for the advancement of the development of new drugs for Alzheimer’s disease,” he explained. The organization ensures that every cent of each dollar donated goes towards drug research, with no deductions for administrative costs, salaries, rent, legal fees or overhead. “Our donors get the advantage of having a big impact with their donations,” Fillit said.

Alzheimer’s disease continues to be the common form of dementia, affecting roughly 6 million Americans. In 2022, costs associated with treating the condition were approximately $321 billion and could top $1 trillion by 2050, according to the American Journal of Managed Care.

Developing successful drugs for Alzheimer’s has proven elusive for most of the past two decades. Fillit noted that since 2000, the failure rate for Alzheimer’s drug development has been close to 100%. In 2021, aducanumab was the first drug to win a regulatory nod in nearly 20 years. But controversy ultimately surrounded FDA’s accelerated approval of the drug, given the drug’s high cost and mixed evidence of its safety and efficacy.

Expanding the horizons of Alzheimer’s research: The diverse drug pipeline

There is, however, reason for optimism concerning Alzheimer’s drug development. For one thing, there is burgeoning interest in Alzheimer’s research. In January, FDA granted accelerated approval to Eisai and Biogen’s Leqembi (lecanemab-irmb). Additionally, the pipeline of Alzheimer’s drugs has grown more diverse in the past several years. “There are somewhere between 120 to 140 Alzheimer’s drugs in clinical development now, and for the first time, the vast majority of these — about 75% to 80% are for non-amyloid, non-tau targets,” Fillit said.

Clinical trial improvements in Alzheimer’s research

Clinical trials for Alzheimer’s drug candidates have also improved in recent decades. “I’ve been in the field for over 40 years, and I remember the days when we didn’t really know how to diagnose people,” Fillit said.

The growing reliance on biomarkers has enabled clinical trial researchers to be more selective. “We know now that probably 30% to 35% of people that were recruited prior to the days when we had these biomarkers or PET scans for beta amyloid and blood tests and spinal fluid tests didn’t have Alzheimer’s disease, even though they were recruited and enrolled by experts,” Fillit said.

The situation has improved considerably over the past five to 10 years, Fillit said, thanks to the availability of highly reliable biomarkers encompassing PET scans for beta-amyloid, blood tests and cerebrospinal fluid examinations.

The availability of such biomarkers helped pave the way for the FDA approval of recent monoclonal antibodies, but the high cost of those drugs may limit their uptake. “They’re showing us the way towards effective treatments on one particular target right now, which is the beta amyloid,” Fillit said. “But I think we’re going to need the next generation of these monoclonals being subcutaneous at-home injections instead of going to infusion centers,” he added. “Ultimately, we could have small molecule pills that will treat the beta amyloid pathway effectively and we have invested in a few companies that are doing that at this point in time.”

Prevention in Alzheimer’s research: the rise of lifestyle interventions

“I think the other story here is prevention,” Fillit said. There has been an explosion of prevention research in the field over the past 20 years.

The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER) study is one example, yielded insights into the role of multi-domain approaches, including proper nutrition, exercise, cognitive training, and management of vascular risk factors, can prevent or delay Alzheimer’s. The study, conducted between 2009 and 2011, was summarized in The Lancet in 2015.

The FINGER trial also has inspired another international trial, known as WW-FINGERS, which aims to replicate its success in countries throughout the world.

Another study, which Fillit dubs FINGER 2.0, is officially called the MET-FINGER.

The MET-FINGER study expands on these findings, merging healthy lifestyle alterations with a diabetes drug (metformin) to examine possible dementia prevention. With around 600 participants, the study will analyze the joint impact of lifestyle modifications and metformin on dementia risk reduction in older adults. Fillit mentioned that metformin could potentially combat insulin resistance in the aging brain and slow neurodegeneration.

Fillit compared this approach to counseling heart disease patients to exercise, follow a Mediterranean diet, sleep well, avoid stress, and abstain from smoking or drinking. In addition, if they have high cholesterol, a statin is prescribed. The model suggests that maintaining a healthy lifestyle, staying socially engaged, and keeping the brain active are beneficial. Metformin, an anti-aging drug with multiple effects, will also be prescribed. “The model here is that it is good to do all those good things — and stay socially engaged and keep your brain active,” Fillit said. “On top of that, we’re going to prescribe metformin, an anti-aging drug that has pleiotropic effects.”

The impact of modifiable risk factors

In 2020, the Lancet Commission concluded that a dozen modifiable risk factors contribute to roughly 40% of global dementia cases.

The discoveries pertaining to modifiable risk factors could complement researchers’ efforts to explore the development of new treatments for Alzheimer’s.

With the support from the Lauder family’s donation, Dr. Fillit and his team of experts will continue their pursuit of advances in Alzheimer’s research. “We have a very deep bench of neuroscientists that are spending their workday every day funding new projects from anywhere in the world that have interesting targets and good data,” he said. “This is what we do for a living.”

Filed Under: Neurological Disease