A team of scientists found a way to create a novel drug delivery system for an array of different conditions.

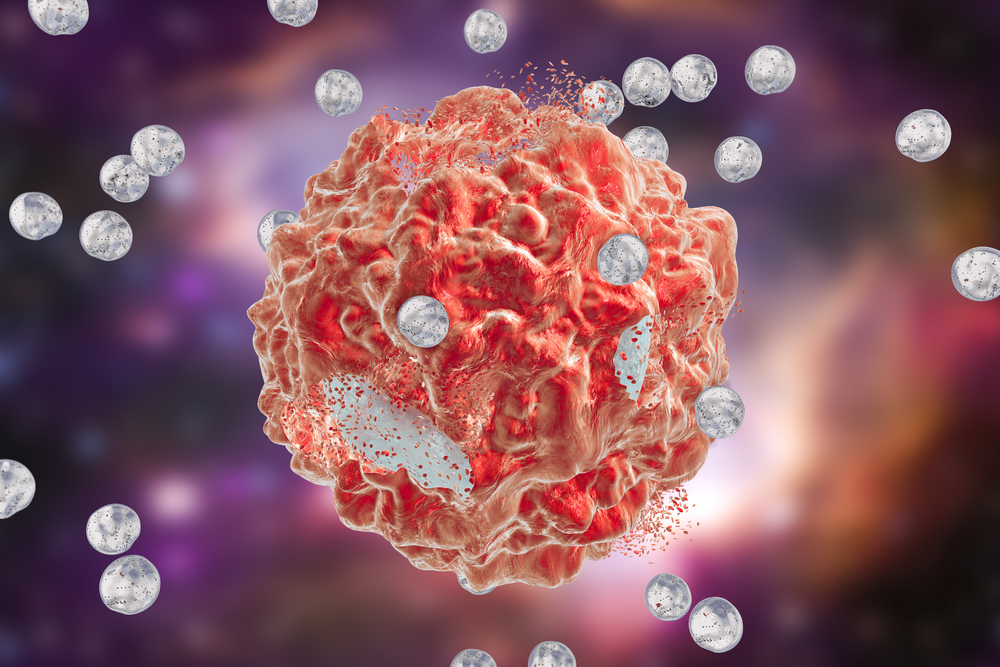

Researchers at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center developed a biomedical tool that harnesses nanoparticles to deliver transient gene changes to specified cells.

This system extends the therapeutic potential of messenger RNA (mRNA). This biological element is responsible for delivering molecular instructions from DNA to other cells in the body making them produce proteins to prevent or attack a disease.

The technique involves mixing freeze-dried nanoparticles with water and a sample of cells.

“Our goal is to streamline the manufacture of cell-based therapies,” said lead author and biomaterials expert Dr. Matthias Stephan, a faculty member in the Fred Hutch Clinical Research Division, in a statement. “In this study, we created a product where you just add it to cultured cells and that’s it — no additional manufacturing steps.”

Here’s how this technology worked in three experiments targeting T-cells in the immune system and blood stem cells in a process they called “hit-and-run” genetic programming.

The team imbued these nanoparticles with a gene editing tool and sent them to T-cells residing in the immune system to snip out their natural T-cell receptors. They were then paired with genes encoding a CAR, otherwise known as a chimeric antigen receptor, designed to attack cancer.

Next, the researchers engineered the nanoparticles to target blood stem cells. They were equipped with mRNA that enabled the stem cells to multiply and replace blood cancer cells with healthy cells when used in bone marrow transplants.

Finally, the nanoparticles were targeted to CAR-T cells containing foxo1 mRNA that signaled to the anti-cancer T-cells to develop into a form of “memory” cell that exhibits more aggressive behavior and destroys tumor cells more effectively.

Other attempts to engineer the mRNA into disease-fighting cells were more difficult. The large messenger molecules degraded quickly before it could make it have an effect while the body’s immune system recognized it as foreign.

Still, this process could replace the more labor-intensive alternative called electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms.

Stephan is currently looking for commercial partners to help move into clinical trials.

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Filed Under: Drug Discovery