A modified version of the Clostridium novyi (C. novyi-NT) bacterium can produce a strong and precisely targeted anti-tumor response in rats, dogs and now humans, according to a new report from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers.

A modified version of the Clostridium novyi (C. novyi-NT) bacterium can produce a strong and precisely targeted anti-tumor response in rats, dogs and now humans, according to a new report from Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center researchers.In its natural form, C. novyi is found in the soil and, in certain cases, can cause tissue-damaging infection in cattle, sheep and humans. The microbe thrives only in oxygen-poor environments, which makes it a targeted means of destroying oxygen-starved cells in tumors that are difficult to treat with chemotherapy and radiation. The Johns Hopkins team removed one of the bacteria’s toxin-producing genes to make it safer for therapeutic use.

For the study, the researchers tested direct-tumor injection of the C. novyi-NT spores in 16 pet dogs that were being treated for naturally occurring tumors. Six of the dogs had an anti-tumor response 21 days after their first treatment. Three of the six showed complete eradication of their tumors, and the length of the longest diameter of the tumor shrunk by at least 30 percent in the three other dogs.

Most of the dogs experienced side effects typical of a bacterial infection, such as fever and tumor abscesses and inflammation, according to a report on the work published online in Science Translational Medicine.

In a Phase 1 clinical trial of C. novyi-NT spores conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center, a patient with an advanced soft tissue tumor in the abdomen received the spore injection directly into a metastatic tumor in her arm. The treatment significantly reduced the tumor in and around the bone. “She had a very vigorous inflammatory response and abscess formation,” according to Nicholas Roberts. “But at the moment, we haven’t treated enough people to be sure if the spectrum of responses that we see in dogs will truly recapitulate what we see in people.”

“One advantage of using bacteria to treat cancer is that you can modify these bacteria relatively easily, to equip them with other therapeutic agents, or make them less toxic as we have done here,” said Shibin Zhou, associate professor of oncology at the Cancer Center. Zhou is also the director of experimental therapeutics at the Kimmel Cancer Center’s Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics. He and colleagues at Johns Hopkins began exploring C. novyi’s cancer-fighting potential more than a decade ago after studying hundred-year old accounts of an early immunotherapy called Coley toxins, which grew out of the observation that some cancer patients who contracted serious bacterial infections showed cancer remission.

The researchers focused on soft tissue tumors because “these tumors are often locally advanced, and they have spread into normal tissue,” said Roberts, a Ludwig Center and Department of Pathology researcher. The bacteria cannot germinate in normal tissues and will only attack the oxygen-starved or hypoxic cells in the tumor and spare healthy tissue around the cancer.

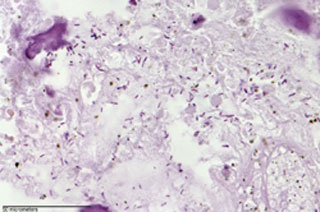

Verena Staedtke, a Johns Hopkins neuro-oncology fellow, first tested the spore injection in rats with implanted brain tumors called gliomas. Microscopic evaluation of the tumors showed that the treatment killed tumor cells but spared healthy cells just a few micrometers away. The treatment also prolonged the rats’ survival, with treated rats surviving an average of 33 days after the tumor was implanted, compared with an average of 18 days in rats that did not receive the C. noyvi-NT spore injection.

The researchers then extended their tests of the injection to dogs. “One of the reasons that we treated dogs with C. novyi-NT before people is because dogs can be a good guide to what may happen in people,” Roberts said. The dog tumors share many genetic similarities with human tumors, he explained, and their tumors appeared spontaneously as they would in humans. Dogs are also treated with many of the same cancer drugs as humans and respond similarly.

The dogs showed a variety of anti-tumor responses and inflammatory side effects.

Zhou said that study of the C. novyi-NT spore injection in humans is ongoing, but the final results of their treatment are not yet available. “We expect that some patients will have a stronger response than others, but that’s true of other therapies as well. Now, we want to know how well the patients can tolerate this kind of therapy.”

It may be possible to combine traditional treatments like chemotherapy with the C. novyi-NT therapy, said Zhou, who added that the researchers have already studied these combinations in mice.

“Some of these traditional therapies are able to increase the hypoxic region in a tumor and would make the bacterial infection more potent and increase its anti-tumor efficiency,” Staedtke suggested. “C. novyi-NT is an agent that could be combined with a multitude of chemotherapy agents or radiation.”

“Another good thing about using bacteria as a therapeutic agent is that once they’re infecting the tumor, they can induce a strong immune response against tumor cells themselves,” Zhou said.

Previous studies in mice, he noted, suggest that C. novyi-NT may help create a lingering immune response that fights metastatic tumors long after the initial bacterial treatment, but this effect remains to be seen in the dog and human studies.

Date: August 13, 2014

Source: Johns Hopkins Medicine

Filed Under: Drug Discovery