Government research agencies, academic institutions, and large (and small) pharmaceutical, biotech, sequencing, and diagnostic companies continue to explore links between genetic variability and common diseases with the goal of developing targeted drugs and therapies. While researchers remain generally optimistic about the future of “personalized medicine,” there is a growing debate over the utility of using genome-wide association studies to identify genetic risks and causes of common diseases.

Government research agencies, academic institutions, and large (and small) pharmaceutical, biotech, sequencing, and diagnostic companies continue to explore links between genetic variability and common diseases with the goal of developing targeted drugs and therapies. While researchers remain generally optimistic about the future of “personalized medicine,” there is a growing debate over the utility of using genome-wide association studies to identify genetic risks and causes of common diseases.

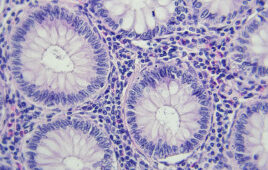

Over the past 20 years, more than 100 genome-wide association studies have been conducted, exploring more than 40 diseases and identifying hundreds of risk-inducing polymorphisms. Dozens of private companies and institutes have established their own research projects targeting conditions such as HIV, diabetes, schizophrenia, cancer, and central nervous system diseases, based on these and other genetic studies. Physicians can use pharmacogenetic tests to help devise treatment regimens for patients with leukemia, breast cancer, and heart disease, among others. Drug manufacturers have used pharmacogenetic studies to modify dosing information for irinotecan (Camptosar, Pfizer) for colorectal cancer, mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Teva Pharmaceuticals) for inflammatory bowel disease and childhood leukemia, and warfarin (Coumadin, Bristol-Meyers Squibb) to prevent heart attacks and strokes. The emerging problem is that the genetic components of common diseases appear to be far more complex than previously thought. The vast majority of newly identified genetic risk-markers, for instance, are associated with only very small relative risks for those diseases. It may be that common diseases such as cancer and diabetes implicate a large number of rare genetic variants, rather than a few common ones. “Common variation is packing much less phenotypic punch than expected,” said David B. Goldstein, PhD, director of Duke University’s Center for Human Genome Variation (Durham, NC). “In pointing at everything, genetics would point at nothing,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine (April 23, 2009).

Initial genome-wide association studies of common diseases are worthwhile, Goldstein says, because they can identify the strongest determinants of common variants. Studies have helped explain the heritability of macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s, and exfoliation glaucoma. Beyond this, their value approaches diminishing returns, “where there are probably either no more common variants to discover or no more that are worth discovering,” he said.

This may actually be good news for drug discovery: genomic scans have not yet been performed in searches for variants involved in responses to many infectious agents or drugs, including those for diabetes and HIV.

Instead of conducting more wide-association studies, however, Goldstein suggests shifting emphasis to full-genome scans of selected individuals to help identify rare variants that will, in turn, suggest novel therapeutic targets as well as personalized prevention and treatments.

Peter Kraft, PhD, and David J. Hunter, ScD, professors at the Harvard School of Public Health (Boston, Mass.), wrote a NEJM article agreeing with Goldstein that many genetic variants, rather than a few, are responsible for most of the inherited risks of common diseases. They disagreed with his assertion of diminishing values of association studies. The authors said that meta-analyses of pooled results from multiple studies have led to the discovery of new loci associated with small increases in the risks of major diseases, including more than 16 new loci associated with diabetes and over 30 linked to Crohn’s disease. “From a scientific perspective, we would like to know roughly how many risk loci remain to be discovered,” they wrote.

Despite the debate, government agencies including the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and companies of all sizes continue to have confidence in the value of personalized medicine. “Today, there is hardly a compound in development anywhere for which there’s not also a biomarker discovery program to find out for whom the drug works and for whom it does not, in an effort to develop safer and more efficacious drugs that meet patient needs,” said Edward Abrahams, PhD, executive director of the Personalized Medicine Coalition (PMC), a Washington, DC-based nonprofit consortium with more than 160 academic, pharmaceutical, biotech, diagnostic, and patient advocacy companies.

In addressing the PMC’s annual conference in March, Paul Stoffels, MD, group chairman of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, described how combining diagnostic and therapeutic technologies allows his company to take a personalized approach to HIV, metastatic cancer, and diseases of the central nervous system. “A lot of people think that going for personalized medicine is limiting the possibilities on drug development. I think it is the opposite. It is the future on how new drugs should be developed,” Stoffels said.

New initiatives

There is certainly no shortage of new initiatives. Geneticist Dietrich Stephan, PhD, a former faculty scientist at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), is seeking funding to build a $245-million research institute in Northern Virginia that would focus on personalized medicine. The proposed 300,000-square foot facility, tentatively called the Ignite Institute for Individualized Health, would employ up to 500 scientists in collaboration with George Washington University, George Mason University, and Inova Health System.

Already underway in North Carolina is the MURDOCK study, for Measurement to Understand the Reclassification of Disease of Cabarrus and Kannapolis. David H. Murdock, the billionaire owner of Dole Food Company, Inc., gave $35 million to Duke University in 2007 to fund the first five years of the study, which aims to identify genomic linkages across major chronic diseases and disorders.

Organizers compare the MURDOCK study to the 1948 Framingham Heart Study that followed generations of residents of that Massachusetts town and generated extensive knowledge about heart disease. The MURDOCK study hopes to recruit 50,000 people from the Cabarrus and Kannapolis areas of North Carolina, sequence their genomes, and identify associations to disease. “The study will mostly focus on biomarkers,” said Sheetal Ghelani, PhD, business development manager of the David H. Murdock Research Institute in Kannapolis. “This longitudinal study seeks to advance personalized medicine.”

About the Author

Contributing editor Ted Agres, MBA, is a veteran science writer in Washington, DC. He writes frequently about the policy, politics, and business aspects of life sciences.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics