Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), an inherited disorder that causes vision loss starting in childhood, improved patients’ eyesight and the sensitivity of the retina within weeks of treatment. Both of these benefits, however, peaked one to three years after treatment and then diminished, according to results from an ongoing clinical trial funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), an inherited disorder that causes vision loss starting in childhood, improved patients’ eyesight and the sensitivity of the retina within weeks of treatment. Both of these benefits, however, peaked one to three years after treatment and then diminished, according to results from an ongoing clinical trial funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI), part of the National Institutes of Health.

The results published online in the New England Journal of Medicine focus on a subset of trial participants who routinely underwent extensive tests of their vision and imaging of the retina from baseline up to six years after treatment. These in-depth examinations revealed that the areas of treated retina rapidly gained visual sensitivity, expanded and then contracted.

“Gene therapy for LCA demonstrated we could improve vision in previously untreatable and incurable retinal conditions,” said Samuel G. Jacobson, M.D., Ph.D., who led the clinical trial at the University of Pennsylvania’s Scheie Eye Institute, Philadelphia. “Even though the current version of the therapy doesn’t appear to be the permanent treatment we were hoping for, the gain in knowledge about the time course of efficacy is an opportunity to improve the therapy so that the restored vision can be sustained for longer durations in patients.”

The results contribute to the bigger picture of the potential benefits – and remaining problems to solve – in the field of gene therapy for LCA and other diseases that affect the retina, the light-sensitive tissue in the eye.

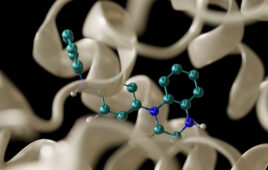

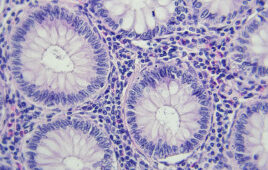

About 10 percent of people with LCA carry a mutated form of the gene RPE65, which makes a key protein found in the retinal pigment epithelium, a layer of cells that nourish the light sensors or photoreceptor cells of the retina. The RPE65 protein is critical for vision. In the retina, millions of photoreceptors detect light and convert it into electrical signals that are ultimately sent to the brain. Photoreceptors rely on the RPE65-driven visual cycle to recharge their light sensitivity. They also need RPE65 for their long-term survival. In LCA, the cells eventually die, muting eye-to-brain communication.

Dr. Jacobson along with Artur V. Cideciyan, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania, and William W. Hauswirth, Ph.D., University of Florida, Gainesville, began the trial in 2007. Fifteen people with LCA received retinal injections of a harmless virus engineered to carry healthy RPE65 genes. This gene therapy relies on viral vectors as a means to deliver instructions for making the desired protein. In this case, the virus was designed to produce healthy RPE65. Dr. Hauswirth led the group that designed and produced the virus-gene material for testing in patients.

“Within days of the injections, some patients reported increases in their ability to see dim lights they had never seen before. It was remarkable for us to get this feedback that things were indeed changing positively,” said Dr. Jacobson.

In addition to the rapid onset of greater light sensitivity, the researchers discovered changes to another component of vision that occurred slowly. Four of the 15 patients started relying on an area of the retina near the gene therapy injection site for seeing letters. Normally, the fovea with its high density of photoreceptors is responsible for seeing fine details.

“For some patients, preferential use of the treated area for seeing letters came about spontaneously about a year after the gene therapy and remained functional for up to six years,” said Dr. Cideciyan, who reported these findings in Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science in January.

For the current study, Dr. Jacobson’s team also examined the relationship between structure and function in the retina. Importantly, these results showed that photoreceptors continued to die at the same rate as they do in the natural course of the disease, regardless of treatment. The researchers concluded that gene therapy with RPE65 boosted the visual cycle, but did not delay photoreceptor cell death. Hence, the short-term gains in visual function.

“We now have six years of data showing that a gene therapy approach is safe and that it successfully improves vision in people with this blinding disease,” said Paul A. Sieving, M.D., Ph.D., director of NEI. “As with any application of a novel therapy, it now needs to be fine-tuned. More research is needed to understand the underlying biology and how we can preserve or restore photoreceptors for a lifetime. Restoring vision is at the heart of the NEI’s Audacious Goals Initiative, an effort to strategically fund research aimed at developing the knowledge and technology to make this goal a reality.”

Dr. Jacobson’s latest results are consistent with another independent investigation performed at Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College London. Those investigators found that retinal sensitivity improved in their LCA patients treated with gene therapy, but then it diminished after 12 months.

The current findings suggest a number of potential strategies for improving the outcome of gene therapy, Dr. Jacobson said. For example, the ability to stage the disease prior to gene therapy would help clarify the potential benefits for each individual. The treatment could then be guided to retinal areas that contain enough functional photoreceptors to respond. Select patients may benefit from a second round of gene therapy, or from having an adjacent area of the retina treated, or from combining gene therapy with medications designed to boost the visual cycle or to protect the retina from cell loss.

“We’ve been able to positively alter and extend the visual life of patients with LCA, and we now have to develop workable strategies for extending it even further,” Dr. Jacobson said.

Source: National Eye Institute

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics