University of Michigan researchers have discovered that a common parasite infecting one in five Americans needs an escape hatch to go on its destructive mission that can damage the brain, eyes, and other organs.

The protozoan parasite called Toxoplasma gondii infects up to 23 percent of Americans. In some areas of the world, up to 95 percent of the population serves as host to this parasite, which causes toxoplasmosis, a serious infection that can lead to birth defects, eye disease, and life-threatening encephalitis.

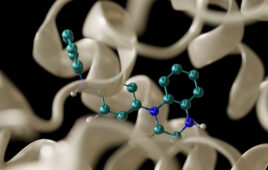

UM researchers report the protein called TgPLP1 is responsible for helping the parasite spread infection. This research breakthrough may one day aid in developing drugs or vaccines to treat or prevent toxoplasmosis or related diseases, including malaria.

‘For some time we’ve been interested in how this parasite successfully enters cells,’ says Vern B. Carruthers, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the U-M Medical School.

‘A couple of years ago, we identified several new proteins secreted by the parasite. Among these was TgPLP1, which captured our interest because it is related to proteins of our own immune system responsible for warding off infection and cancer,’ Carruthers explains.

After the initial period of infection, which may cause mild flu-like symptoms, Toxoplasma gondii goes on to lie dormant in a person’s brain and central nervous system. But if a person’s immune system becomes compromised, such as from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or organ transplant surgery, the Toxoplasma infection can be reactivated.

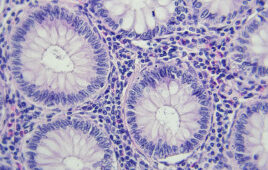

In an immunocompromised person, Toxoplasma gondii amplifies the infection by invading a cell and undergoing several rounds of replication within that cell. ‘Then it has to escape from the cell in order to find and infect additional cells,’ Carruthers explains.

TgPLP1 is a type of protein responsible for forming pores, or small openings, in the cell membrane to allow the parasite to escape and cause disease more rapidly throughout the host.

Research details

Carruthers’ research team pinpointed how TgPLP1 works by generating and observing a cultured parasite that does not have the TgPLP1 protein. While observing the movements of the mutant parasite with video microscopy, the team noticed that, compared to the normal parasite, the parasite without TgPLP1 struggled to get out of the host cells and remained trapped within the cell membrane.

The research team offers several theories as to how the protein enhances the parasite’s ability to cause disease.

‘We think that this protein helps the parasite escape by weakening the membranes that encase the parasite during replication,’ says Bjorn F.C. Kafsack, Ph.D., a research fellow in U-M’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology and the study’s first author. ‘It’s also possible that TgPLP1 works by allowing other proteins to break out ahead of the parasite. These other proteins could digest components of the host cell that serve as barriers to the parasite getting out of the host cell.’

Even when infected host cells were treated with a drug that would normally trigger the parasite to leave, TgPLP1-deficient parasites had difficulty or failed to exit from the host cell.

For the next stage of the research, the team injected mice with the TgPLP1-deficient parasites. ‘The mutant parasites grow quite quickly when we culture them in the lab but when we infect mice with them, they’re severely weakened,’ a fact that came as a surprise, Kafsack says.

Significantly more TgPLP1-deficient parasites were needed to cause disease in the mice, compared to the normal parasites, researchers found.

‘It implies that the ability of the parasite to quickly escape from its old host cell is a critical step during infection of animals,’ Kafsack says.

Implications

Now that researchers know the purpose and importance of this protein for the disease, they may find ways of interfering with its functions, such as finding a selective treatment that disables the parasite protein and therefore slows or stops Toxoplasma gondii’s spread.

Using the gene-deleted mutants developed in this research against Toxoplasma gondii, scientists may eventually be able to develop a vaccine against this common infection, Carruthers says.

‘Because the gene deletion mutants are so weakened, they could be used as a vaccine strain to initiate an immune response that may be protective, but without persisting or causing disease as the normal parasites would,’ Carruthers says.

This research may also offer insights into how the parasite that causes malaria might spread and cause infection.

‘Because the malaria parasite has proteins similar to the one in the study, it may also use a pore-forming protein to escape from infected red blood cells,’ Carruthers says. Better understanding these mechanisms may someday help researchers develop new strategies for controlling the spread of the disease.

Release Date: January 26, 2009

Source: University of Michigan Health System

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics