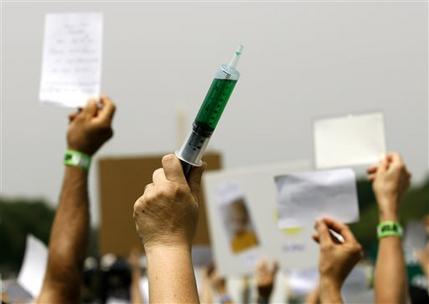

Certain that they are right, struggling to find ways to get their message across, public health officials are exasperated by their inability to convince more U.S. parents to vaccinate their children.

Certain that they are right, struggling to find ways to get their message across, public health officials are exasperated by their inability to convince more U.S. parents to vaccinate their children.“I think we’re all kind of frustrated,” said Stephen Morse, a Columbia University infectious disease expert. “As scientists, we’re probably the least equipped to know how to do this.”

They say they are contending with a small minority of parents who are misinformed – or merely obstinate – about the risks of inoculations. The parents say they have done their own research and they believe the risks are greater than health authorities acknowledge; they are merely making their own medical choices, they say.

Most parents do bring their children for shots, and national vaccination rates for kindergarteners remain comfortably above 90 percent. Experts aren’t even sure the ranks of families who don’t vaccinate are growing to any significant degree.

But in some states, the number of parents seeking exemptions from school attendance vaccination requirements has been inching up. In some communities, large proportions of household skip or delay shots. The rise has come despite unsettling outbreaks of some vaccine-preventable diseases that had nearly disappeared from the United States.

“Part of the reason everyone is so concerned about this is because they don’t know whether things will get worse,” said Dr. Walter Orenstein of Emory University, considered one of the nation’s leading experts on vaccines.

Measles is a leading worry. A little over 50 years ago, measles caused nearly a half a million illnesses in the United States each year, including about 450 deaths. But decades of vaccination campaigns put an end to homegrown measles transmission by 2000. Annual reported illnesses dropped as 34, in 2004. But in the last five years or so, cases jumped back into the hundreds as infected travelers sparked outbreaks in poorly vaccinated communities.

Right now the number of cases remains relatively small. But health officials fear that if the number of unvaccinated families keeps growing, sustained spread of measles will be re-established in the United States, and it will become a native virus once again. “That’s what we don’t want to happen again,” Orenstein said.

Scientists have long assumed the problem is that some parents are simply misinformed, and providing them “corrective information” will clear things up.

But some studies have shown that doesn’t seem to work. For example, in the last 15 years, a leading concern of many vaccine opponents is that shots trigger autism in children. One recent study found that some vaccine-opposed parents could be presented with medical evidence disproving that, and seemed persuaded. But they also said they still did not intend to vaccinate their kids.

“People are really good at coming up with reasons to believe what they already believe,” said Jason Reifler, a political scientist at the University of Exeter who co-authored the study.

In fact, vaccines can have side effects – very severe ones, in extremely rare cases that doctors can’t always anticipate. “It may be one in a million or one in 2 million, but I can’t tell you that it won’t happen to your child,” Morse said.

Some parents say, “I’m not willing to take that chance with my child,” he added.

Parents have been nervous about vaccines for as long as vaccines have been around – at times with good reason. More than 100 years ago, vaccines were unregulated and could be as likely to harm a child as protect them. Opposition seemed to plummet for several decades, as vaccines got better and succeeded in beating back diseases that had long terrified families, including polio, measles and whooping cough.

But parental concern has seemed to be on an upswing in the last 20 years.

Family decisions about vaccinations have always involved a cost-benefit analysis, in which parents weight the danger of the disease against side effects or other potential risks from the vaccine itself. As overall vaccination rates hit high levels and diseases became rare, some families have decided the risks of vaccination outweigh the benefits, observed Massachusetts General Hospital’s Dr. Stephen Calderwood, president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Meanwhile, the rise of the Internet meant people suspicious of the government, doctors and pharmaceutical companies were given an electronic megaphone to share their beliefs. Bolstered by a 1998 study in a British medical journal that suggested a link between autism and the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, vaccine skeptics grew louder and louder – even after the British paper was discredited and retracted.

It didn’t help that autism prevalence rates continued to steadily increase, and that health officials haven’t been able to determine exactly what’s causing that. They say increased diagnosing of the condition is part of the story, but probably not all of it.

It also may not help that when vaccine opponents raise an unlikely concern, government scientists have often declined to debate them or say they were flat-out wrong if there was no medical evidence available yet to answer a claim.

“It probably hurts” the cause of vaccination, Reifler said, when opponents sound certain in their alarms about vaccine while scientists more cautiously say “all the evidence that we have is that’s not true,'” but the hypothesis can’t be completely ruled out, he said.

Meanwhile, scientists are finding it harder to make a case for new childhood vaccines. The CDC and its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is currently considering whether to recommend two newly licensed vaccines against B strain meningococcal bacteria, a bug that can cause meningitis and blood infections. The diseases are horrible – even with antibiotic treatment, an alarmingly high 10 to 15 percent of people who get meningococcal disease die, and about 15 percent of survivors have long-term disabilities, including loss of limbs or brain damage.

But such illnesses are rare: one estimate suggests widespread B strain vaccination for all adolescents and young adults would prevent only 30 to 40 U.S. illnesses a year, including three or four deaths. What’s more, the new vaccines are expensive, given in series of shots that cost more than $300 at retail prices.

But in deciding whether to go ahead with approval of the vaccines, another consideration is the reaction of parents who don’t even have faith in current vaccines and cringe each time another shot is added to the roster.

The CDC and its advisory panel have to balance the benefits and the risks in a way that maintains public trust, and doesn’t alienate more families, said Robert Aronowitz, professor and chair of the history and sociology of science department at the University of Pennsylvania.

“These are very, very difficult decisions,” he said.

Experts see the cooperation of physicians as a key to prodding families to get old and new vaccines. They believe too many family physicians and pediatricians have been lax. Some doctors perhaps see themselves as too busy to spend time debating the value of vaccines with resistant families. Some have complained about the cost and hassle of stocking the shots. A smaller contingent may have their own questions about vaccine, and indulge families that want to postpone or skip shots.

ACIP has been looking at the problem. So has another national panel – the National Vaccine Advisory Committee, chaired by Orenstein – which two years ago convened a Vaccine Confidence Working Group to study the issue. In a draft set of recommendations presented this month, the group said there’s not enough good information on where clusters of unvaccinated people are, to what extent they are growing, and why they exist.

The workgroup is recommending more study, and better training of physicians so that they will work harder to present childhood vaccination as the sensible way to go.

Another strategy is to simply make more parents vaccinate, through a concerted effort to eliminate philosophical exemptions to vaccinations or to make the exemption application process more demanding. Several experts interviewed believed reducing exemptions is the most practical approach, in a country where individual freedoms are sometimes celebrated at the expense of the communal good.

“No other country relies on mandatory vaccinations as significantly as the U.S. does to insure high rates of vaccination,” Schwartz said.

“One argument is we need those mandates,” he said.

Filed Under: Drug Discovery