A team of scientists from UC San Francisco and Mayo Clinic has shown that using just three molecular markers will help clinicians classify gliomas – the most common type of malignant brain tumors – more accurately than current methods.

A team of scientists from UC San Francisco and Mayo Clinic has shown that using just three molecular markers will help clinicians classify gliomas – the most common type of malignant brain tumors – more accurately than current methods.In a study published online June 10 by The New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers report that, based on the presence or absence of each marker, 95 percent of gliomas fall into one of five distinct groups, which vary in terms of median survival times and other characteristics.

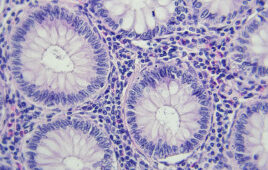

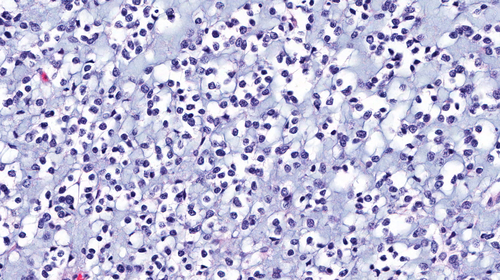

Currently, malignant gliomas are classified based on the appearance of biopsy samples under the microscope, and their grade, or degree of aggressiveness, with grade II being the least aggressive and grade IV the most.

“Unfortunately, classifying a tumor only by appearance and grade has not provided sufficient information about the way the tumor is likely to behave, how it will respond to treatment or the patient’s likely survival time,” said co-senior author Margaret R. Wrensch, PhD, UCSF professor of neurological surgery and epidemiology and biostatistics and the Stanley D. Lewis and Virginia S. Lewis Endowed Chair in Brain Tumor Research. “These markers will potentially allow us to predict the course of gliomas more accurately, treat them more effectively and identify more clearly what causes them in the first place.”

The three markers are a mutation in the region that promotes expression of the gene TERT, which expresses telomerase, an enzyme that helps keep cancer cells alive by protecting structures called telomeres; a mutation in the genes IDH1 or IDH2, referred to collectively as IDH mutation; and a combined mutation that deletes parts of chromosome 1 and chromosome 19.

The study authors analyzed genetic and clinical data from 1,087 malignant glioma patients and 11,590 healthy controls from Mayo Clinic, UCSF and The Cancer Genome Atlas, a program of the National Cancer Institute.

The scientists found that among grade II and III tumors, 29 percent were “triple positive,” showing all three markers. Patients with these tumors had a median survival time of 13.1 years. Five percent had both TERT and IDH mutations, and had a median survival time similar to triple positive tumors. Forty-five percent had IDH mutation only, and a median survival time of 8.9 years. Seven percent of tumors were triple negative, with none of the mutations, and had a median survival time of 6.2 years. The 10 percent of tumors that only had the TERT mutation were associated with the shortest median survival time – 1.9 years.

Wrensch suggested that once these or similar molecular markers are accepted by clinicians as part of the classification system, “it may make a great deal of difference in treatment approach for individual patients.”

She said that under the current system, “someone with a grade III glioma, for example, may not have been treated as aggressively as someone with a grade IV. But now, if you determine that it’s a TERT-mutated-only tumor, there is more confidence that it will behave more like a grade IV tumor and could be treated more aggressively.” In contrast, said Wrensch, “a grade III tumor that only has an IDH mutation might be treated less aggressively. Glioma treatments can be very toxic, so it’s important to know how aggressive treatments need to be.”

The researchers found that among patients with grade IV tumors, age at diagnosis was a more important predictor of survival than molecular subgroup, with younger patients having a better chance of surviving longer than older patients. “We don’t know why that is yet,” said Wrensch. “It might have something to do with the immune system or with telomere maintenance, but we are studying these questions. This study provides a new foundation.”

Source: UCSF

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics