Cancer’s ability to grow unchecked is often attributed to cancer stem cells, a small fraction of cancer cells that have the capacity to grow and multiply indefinitely. How cancer stem cells retain this property while the bulk of a tumor’s cells do not remains largely unknown. Using human tumor samples and mouse models, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center discovered that cancer stem cell properties are determined by epigenetic changes — chemical modifications cells use to control which genes are turned on or off.

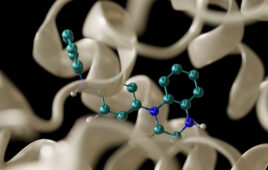

Cancer’s ability to grow unchecked is often attributed to cancer stem cells, a small fraction of cancer cells that have the capacity to grow and multiply indefinitely. How cancer stem cells retain this property while the bulk of a tumor’s cells do not remains largely unknown. Using human tumor samples and mouse models, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center discovered that cancer stem cell properties are determined by epigenetic changes — chemical modifications cells use to control which genes are turned on or off.The study, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reports that an enzyme known as Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1 (LSD1) turns off genes required to maintain cancer stem cell properties in glioblastoma, a highly aggressive form of brain cancer. This epigenetic activity helps explain how glioblastoma can resist treatment. What’s more, drugs that modify LSD1 levels could provide a new approach to treating glioblastoma.

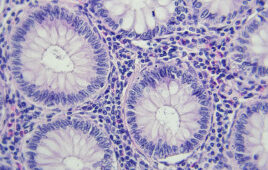

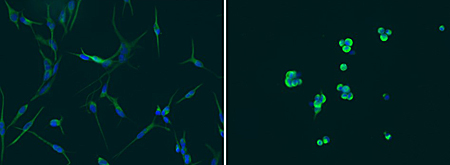

Rresearchers first noticed that genetically identical glioblastoma cells isolated from patients differed in their tumorigenicity, or capacity to form tumors, when transplanted to mouse models. This observation suggested that epigenetics, rather than genetics (DNA sequence), determines tumorigenicity in glioblastoma cancer stem cells.

“One of the most striking findings in our study is that there are dynamic and reversible transitions between tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic states in glioblastoma that are determined by epigenetic regulation,” said senior author Clark Chen, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurosurgery and vice-chair of research and academic development at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Probing further, Chen’s team discovered that the epigenetic factor determining whether or not glioblastoma cells can proliferate indefinitely as cancer stem cells is their relative abundance of LSD1. LSD1 removes chemical tags known as methyl groups from DNA, turning off a number of genes required for maintaining cancer stem cell properties, including MYC, SOX2, OLIG2 and POU3F2.

“This plasticity represents a mechanism by which glioblastoma develops resistance to therapy,” Chen said. “For instance, glioblastomas can escape the killing effects of a drug targeting MYC by simply shutting it off epigenetically and turning it on after the drug is no longer present. Ultimately, strategies addressing this dynamic interplay will be needed for effective glioblastoma therapy.”

Chen and one of the study’s first authors, Jie Li, PhD, note that the epigenetic changes driving glioblastoma are similar to those that take place during normal human development.

“Though most cells in our bodies contain identical DNA sequences, epigenetic changes help make a liver cell different from a brain cell,” said Li, an assistant project scientist in Chen’s lab. “Our results indicate that the same programming processes determine whether a cancer cell can grow indefinitely or not.”

Co-authors of this study also include David Gonda, Valya Ramakrishnan, Miroko Matsui, Olivier Harismendy, Donald Pizzo, Scott Vandenberg, UC San Diego; David Kozono, Masayuki Nitta, Deepa Kushwaha, Dmitry Merzon, Shan Zhu, Kaya Zhu, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Wei Hua, Ying Mao, Shanghai Huashan Hospital; Ichiro Nakano, Chang-Hyuk Kwon, Ohio State University; Hideyuki Saya, and Oltea Sampetrean, Keio University, Japan.

This research was funded, in part, by the Sontag Foundation, Burroughs Wellcome Foundation, Kimmel Foundation, Doris Duke Foundation and Forbeck Foundation.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics