In what is believed to be the largest genetic analysis of what triggers and propels progression of tumor growth in a common childhood blood cancer, researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center report that they have identified a possible new drug target for treating the disease.

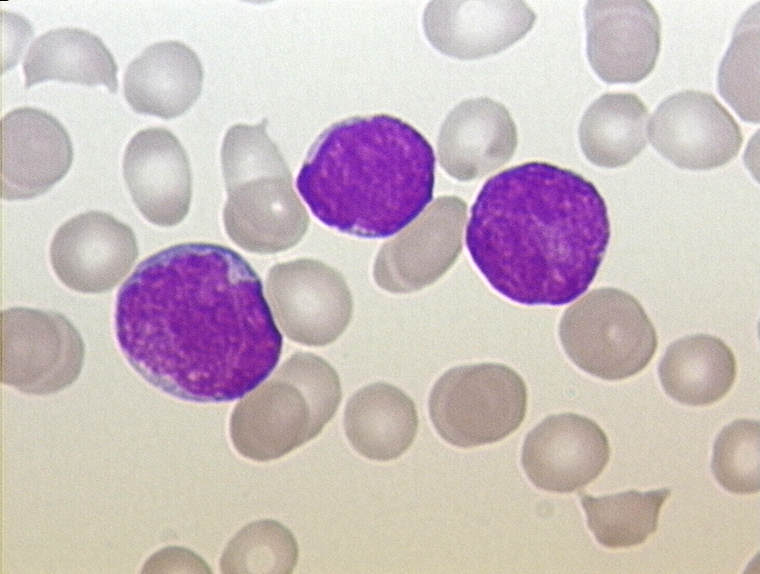

In what is believed to be the largest genetic analysis of what triggers and propels progression of tumor growth in a common childhood blood cancer, researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center report that they have identified a possible new drug target for treating the disease.T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia is one of the most common and aggressive childhood blood cancers. An estimated quarter of the 500 adolescents and young adults diagnosed with the cancer each year in the United States fail to achieve remission with standard chemotherapy drugs.

In a cover-story report set to appear in the journal Cell online, the NYU Langone team describes how they used advanced genetic scanning techniques to identify 6,023 so-called long, non-coding strands of RNA, vital chemical cousins of DNA, that were active in the immune system T cells taken from 15 boys and girls with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but not active in the healthy T cells in three young people without the disease.

Further analysis found that chemically blocking the action of one of those non-protein-producing RNAs, known as leukemia-induced non-coding activator RNA-1, or LUNAR1 for short, stalled leukemia progression.

Study investigators said LUNAR1 was not singled out from RNA typically used by DNA to make proteins, but rather from among the most prevalent RNA— long chemical strands of translated DNA, previously termed “junk DNA”— which can help transcribe DNA but never fully assemble proteins. They said these long non-coding RNAs are increasingly recognized as key to regulating many cell functions.

Senior study investigator and NYU Langone cancer biologist Iannis Aifantis said the study offers preliminary evidence that drugs blocking LUNAR1 could treat T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a long-sought alternative to chemotherapeutic drugs that kill both cancer and normal cells.

Aifantis, a professor and chair of pathology at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at NYU Langone, and an early career scientist at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, also said LUNAR1 could aid in diagnosing the blood cancer.

“Our study shows that LUNAR1 is highly specific for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and plays a key role in how this cancer develops,” he said, pointing out that overproduction of LUNAR1 was recorded in almost all (90 percent) of leukemia patients tested.

Moreover, Aifantis said, his team’s latest findings suggest that development of future cancer therapies based on the underlying genetics of each patient should involve “not just mutations in someone’s DNA, but also alterations in the makeup of RNA.”

Among the study’s other key findings was that while LUNAR1 does not produce cancerous proteins on its own, its production was essential to the cell-to-cell signaling action of another protein, insulin-like growth factor 1receptor (IGF-1R), already tied to many cancers, including leukemia.

Further laboratory experiments showed that the gene coding for LUNAR1 is near the gene for IGF-1R and located toward the chromosomes’ ends, known as telomeres. When activated, LUNAR1’s position allows it to chemically loop back and, in turn, bind to and activate IGF-1R.

Researchers zeroed in on LUNAR1 by pinpointing those RNAs that also were active in the NOTCH1 biological pathway. They said the NOTCH1 pathway is common to many cancers, but is especially active in at least half of all people with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. LUNAR1 stood out right away, they said, as the most highly expressed long, non-coding RNA, of which more than half were newly discovered.

According to Aifantis, his team’s research shows that T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, as is the case in many other cancers, could be simply described as a condition of “too much errant signaling.” He said in normal T cells, the long, non-coding RNAs such as LUNAR1 are not transcribed, NOTCH1 is inactive, and there is no looping back of LUNAR1 to activate IGF-1R.

To confirm their findings, researchers also transplanted human leukemia T cells into mice to prompt tumor growth, and chemically blocked LUNAR1 in some of the animals. Tumor growth stalled only in those mice whose LUNAR1 was inactivated.

Aifantis said his team’s next steps are to develop more effective inhibitors of LUNAR1, preferably something that would precisely target any one or more of its 200-plus component nucleotides.

Date: July 31, 2014

Source: NYU Langone Medical Center

Filed Under: Drug Discovery