It’s easy to feel like clinical trials are complex. They are experiments involving human beings — so things change. But, despite feeling like complexity is everywhere, there is little clarity on what constitutes a complex trial and what sponsors need to do to prepare these trials for success. Both the FDA and EMA, for example, offer somewhat vague definitions of what makes trials complex; the FDA says that designs “intended to advance and modernize drug development” are complex.1 The EMA defines complex trials as having “non-conventional … elements, features, methods … that confer complexity of their designs, conduct, analyses or reporting.” Neither of these definitions provides a practical framework to help sponsors identify what makes trials complex, whether a particular trial meets the criteria, or how to set up complex trials for the greatest chance of success.

It’s easy to feel like clinical trials are complex. They are experiments involving human beings — so things change. But, despite feeling like complexity is everywhere, there is little clarity on what constitutes a complex trial and what sponsors need to do to prepare these trials for success. Both the FDA and EMA, for example, offer somewhat vague definitions of what makes trials complex; the FDA says that designs “intended to advance and modernize drug development” are complex.1 The EMA defines complex trials as having “non-conventional … elements, features, methods … that confer complexity of their designs, conduct, analyses or reporting.” Neither of these definitions provides a practical framework to help sponsors identify what makes trials complex, whether a particular trial meets the criteria, or how to set up complex trials for the greatest chance of success.

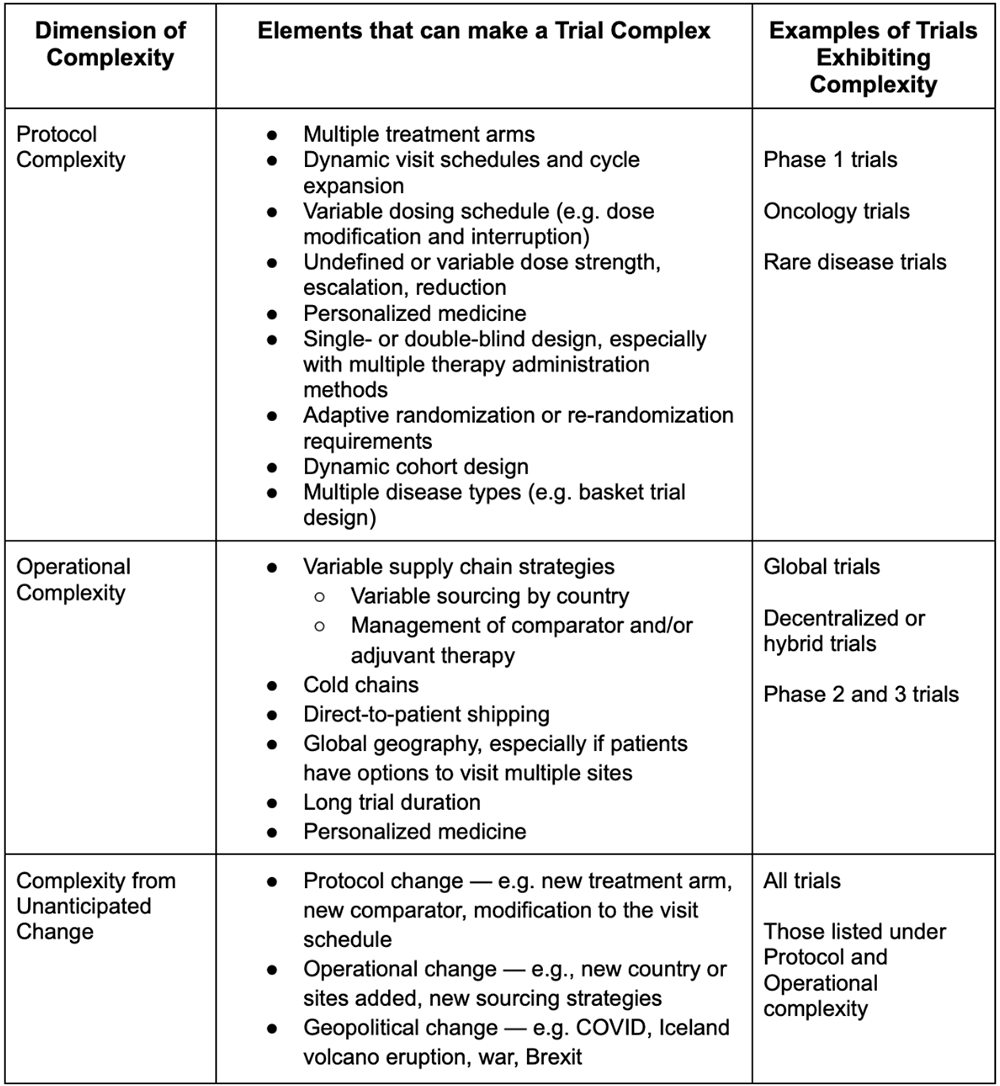

This article aims to fill that gap by providing a framework for complexity in clinical trials. Over Suvoda’s 10 years providing IRT, and more recently eConsent and eCOA, technologies and services to oncology, rare disease, and CNS trials, we have seen the specific elements that can lead to unexpected change and make trials more challenging to manage. Complexity occurs in three dimensions in clinical trials: the protocol, the operations, and the potential for unanticipated change. Trials that are complex in any one of these dimensions require special flexibility to easily adapt to variability and change, including in the technologies built to support the trial.

Unpacking the three dimensions of complexity

Complexity in clinical trials occurs in nearly every therapeutic area, for nearly every sponsor, and in many of today’s trials. Protocol complexity covers intricacies in the study design and can be related to the treatment, patient flow through the study, and point-in-time complexities. Protocol complexities might include things like multiple treatment arms, variable visit schedules, or personalized medicines. Studies that are single- or double-blind require re-randomization or adaptive randomization schemes or add new disease types to the study as it progresses also have significant protocol complexity. Protocol complexity is widespread, and is especially common in early phase studies.

Operational complexity covers complications related to how the study is implemented. It includes things like variable supply chain strategies, direct-to-patient drug shipping, global geography, and trials with extended duration.

Unlike protocol and operational complexity, complexity from unanticipated change is just that: unanticipated. It’s impossible to know what will change, but given that trials are experiments, we can be sure that something will. Unanticipated change can occur in the protocol (e.g., multiple protocol amendments) and the operations (e.g., a new country or region is added). It can also be geopolitical, as we’ve seen in recent years with the war in Ukraine, COVID, or Brexit. See Table 1 for a list of elements that create protocol complexity, operational complexity, and complexity from unanticipated change.

Table 1: A framework for complexity in clinical trials

Complexity in real life: examples from Suvoda’s portfolio

Nearly all of the trials Suvoda supports are complex in at least one dimension, and most fit into two or more types of complexity. This is both because we specialize in complex trials, and because most trials being run today have at least one element that makes them complex.

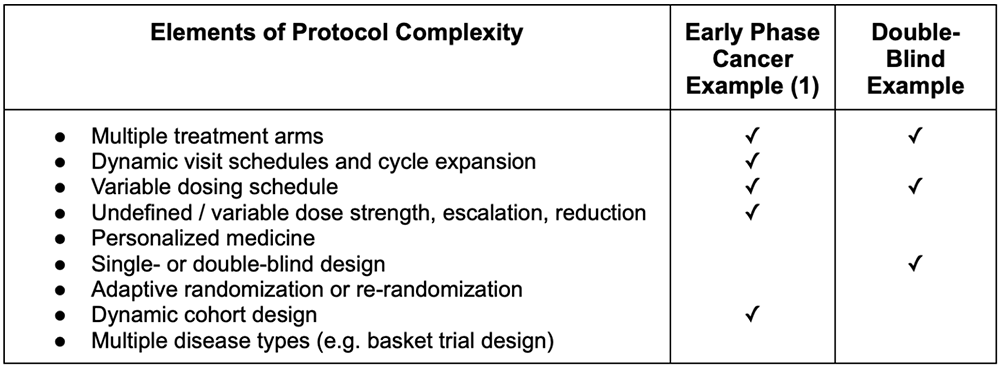

Protocol complexity is prevalent across many studies, sponsors, and therapeutic areas. For example, a recent open-label early-phase cancer trial showed multiple elements of protocol complexity. This particular trial had multiple drug types being tested in various combinations, so the trial had several treatment arms. The various treatment combinations required different visit schedules to accommodate other possible dosing schedules and different cycle lengths. What’s more, as a Phase 1b trial, the enrollment dose strength for each of the different drug types was undefined at the beginning of the trial. This trial also had an undefined number of cohorts to be investigated throughout the study, creating complexity related to the study subjects.

Another study shows what protocol complexity can look like in a double-blinded trial. Because of the double-blind design, the study team needed a highly customized and flexible protocol and IRT design to support different therapy administration routes. Further, the standard of care regimen included two drug types, and one of those types had two different drug options to be used, depending on the diagnosis. In total, the study had to accommodate 10 different drug types, two unique visit schedules, and multiple types of visits for the investigators to manage, all while maintaining the blind. The study was also operationally complex, as subjects were allowed to move between sites for their visits.

Table 2: Elements of protocol complexity in example Suvoda trials

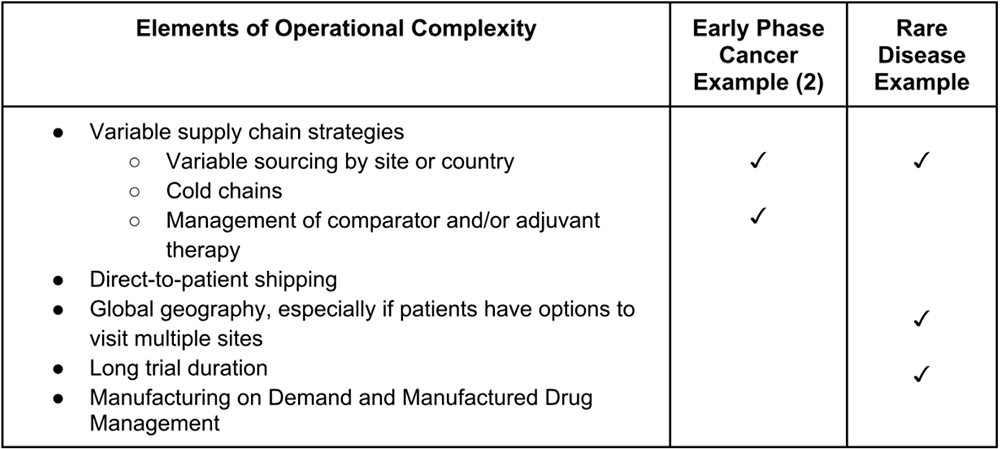

Many studies with protocol complexity also have elements of operational complexity as well. For example, another early phase cancer study examining dose tolerability for two investigational products has many protocol complexities. For instance, the study has multiple treatment arms, dynamic visit schedules and cycle expansion, variable dosing schedules, undefined dose strength, dynamic cohort design, and multiple disease types. It also has additional operational complexity; the study operates in several countries and sites, the standard of care treatment is sourced locally in some countries, but not others, and the two investigational product (IP) drugs are managed and sourced through IRT.

Another trial, this one a multi-country, multi-site Phase 3 study of treatment for a rare disease, has significant operational complexities. As a late-stage trial for a rare disease, the sponsor needed to conduct the trial in multiple locations to have the greatest chance of finding eligible patients close enough to a trial site to participate. The study spanned nearly 80 sites across two dozen countries and has been active for several years. Most sites have enrolled patients, but the vast majority have only a few participants, putting pressure on the supply chain to have enough but not too much drug available across multiple countries and locations. Further, the sponsor allowed patients to receive treatment at multiple sites, reducing as many barriers as possible for patients to participate but increasing complexity for the study team.

Table 3: Elements of operational complexity in example Suvoda trials

In addition to the protocol and operational complexities present in the four example studies, each of them was also affected by complexity from unanticipated change. All of these studies were disrupted in some way by COVID, as were 79% of studies in 2020.3 The war in Ukraine has also impacted many sponsors’ trials; at least 250 studies were running in Ukraine as of May 2022, and as people have fled and defended their country, the integrity of trials and participants’ data and access to treatment are in jeopardy.4 On top of this, trials have unanticipated changes related to their protocols and operations, including protocol amendments and new sites being added while others are shut down.

Implications: Effectively harnessing complexity to drive breakthrough results

Although these trials seem particularly complex, they represent typical scenarios in their respective therapeutic areas. Most Oncology studies require managing multiple drug types, which can lead to changes in cohorts, dosing, and treatments over time. Many studies also have different sourcing and administration methods for IP and standard of care treatments. Nearly all late-stage studies operate across multiple countries and regions. This common complexity found within these studies and many others required the sponsor to think critically about multiple aspects of how the trial would roll out. Although IRT is only one of the many tools sponsors have to take control over complexity, it is an important illustration of the type of preparation needed to make complex clinical trials successful.

In each of the examples above, sponsors and Suvoda worked together to ensure that the IRT systems set up to support these trials built in enough flexibility, visibility, and control to be ready to respond to the variability of the trials. For trials like the early phase cancer study with undefined cohorts, we deployed our advanced cohort management functionality. That allows site users to easily control open cohorts and enrollment limits, as well as add new cohorts and dose levels mid-study. Trials with multiple disease types, like the second early phase cancer example above, used advanced disease type management functionality within IRT to add new disease types to the study in real-time, to open and close disease types for enrollment, and to set enrollment limits by disease type. Dynamic dose and dispensation management, which allows users to add and change dose and dispensation configurations mid-study, is also a functionality we often deploy to prepare for dosing complexities like unknown starting doses, as in both the early phase cancer and the double-blind examples above. And in terms of operational complexity, we often use functionality like supply strategy management, which gives users the flexibility to change supply strategies in real-time for studies like the cancer and rare disease examples with variable supply chains by region. Together, these functionalities add up to sponsors and site users having flexibility, visibility, and control to make real-time adjustments to their clinical operations and clinical supply.

This type of preparation to build in flexibility and control really matters for getting potentially life-saving drugs through the complex clinical trial process and into the hands of patients safely and efficiently. When complex trials are set up with supporting systems and technologies that can adapt to change, those trials run more smoothly. That makes life easier for sites and reduces costly delays for sponsors. At Suvoda, we’ve found that even the many trials with only one or two elements of complexity merit a level of attention and careful implementation similar to highly complex studies. When studies with complex elements are managed with tools designed for simple studies, it can lead to delays, cost increases, and make the process of running the trial more complicated for sites.

Conclusion: Moving forward to take control over complexity

Every clinical trial is an experiment. In experiments, it is typical to explore multiple drug types, test different administration methods, and run studies in various locations across multiple countries. Some adaptations along the way can be planned for, and change also happens that cannot always be anticipated. That’s why flexibility within trial technologies and systems is so important: it allows sponsors to pivot when needed, even when they can’t anticipate it from the outset.

This is an exciting moment in the clinical trials industry; as a field, we have acknowledged that our work is complex, and we’re actively seeking ways to leverage complexity to improve patient outcomes. That starts with thinking critically about what makes trials complex and the ways to respond that give sponsors, sites, and patients the best chance for smooth trials without delays and prohibitive cost increases.

References

- https://www.medpace.com/operationalizing-complex-innovative-trial-design-fdas-new-approach

- https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-06/medicinal_qa_complex_clinical-trials_en.pdf

- https://www.nexsenpruet.com/publication-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-clinical-research-in-life-sciences

- https://www.wired.com/story/war-ukraine-clinical-trials-jeopardy/

Robert Hummel

Robert Hummel is the chief operating officer at Suvoda, a global clinical trial technology company specializing in complex studies in therapeutic areas such as oncology, central nervous system (CNS), and rare disease. Hummel is responsible for global operations at Suvoda. He maintains oversight of the sales and professional services teams worldwide. Prior to Suvoda, Rob held leadership positions with NextDoc Corporation and Clarix/Phase Forward, where he was instrumental in delivering life sciences solutions for clients ranging from small biotechnology firms to large, global pharmaceutical companies and CROs.

Filed Under: clinical trials, Drug Discovery

Tell Us What You Think!

You must be logged in to post a comment.