A Cancer Genomics Browser developed by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, provides a new way to visualize and analyze data from studies aimed at improving cancer treatment by unraveling the complex genetic roots of the disease.

The browser consists of a suite of Web-based tools designed to help researchers find patterns in the huge amounts of clinical and genomic data being gathered in large-scale cancer studies. Medical researchers hope to identify genetic signatures and other biomarkers in cancer cells that can be used to predict how individual patients will respond to different therapies throughout the course of their treatment.

Coauthor, of a paper describing the Cancer Genomics Browser, David Haussler, professor of biomolecular engineering, said development of the browser was driven by the needs of cancer researchers, who are now using powerful technologies for genome analysis and DNA sequencing in their efforts to understand cancer at the molecular level.

‘Each of these tests gives millions of measurements, and the result is a bad case of data overload,’ Haussler said. ‘We’ve built the cancer browser so that researchers can upload their data and use a variety of software tools to visualize and interpret their results.’

To get a user’s perspective on the browser as it took shape, Haussler’s team worked closely with Dr. Laura Esserman, professor of surgery and radiology at UC San Francisco, and Marc Lenburg, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. Esserman and Lenburg, both coauthors of the paper, are involved in the I-SPY Trial, a multi-institutional collaboration aimed at identifying biomarkers to predict the most effective therapies for patients with advanced breast cancer.

‘What is amazing about the browser is that it allows us to combine complex molecular data and clinical observations, and provides insights into how we can truly improve treatment and outcomes,’ said Esserman, director of the Carol Franc Buck Breast Care Center and associate director of the Breast Oncology Program at the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCSF.

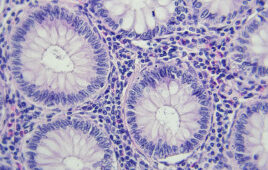

Cancer genomics involves searching for all of the genes and mutations that contribute to the development of a cancer cell and its progression from a localized cancer to metastatic disease that spreads throughout the body. A genome is an organism’s complete set of DNA, and researchers are now able to analyze the alterations that occur throughout the genome of a patient’s cancer cells. Recent advances, such as microarray technology and high-throughput DNA sequencing, have made it possible to characterize tumor samples in exquisite detail.

‘You can run a microarray chip that analyzes a million points in the genome and can tell you about changes in the DNA, as well as inherited variations that make a person more or less susceptible to cancer,’ Haussler said.

Many different types of genomic changes can have clinical significance, including insertions, deletions, and other changes in the DNA sequence, such as changes in the number of copies of a gene. Moreover, microarrays and high-throughput methods for measuring proteins make it possible to see how these genomic alterations interfere with the cell’s normal workings.

‘The Cancer Genomics Browser is fantastic in that it helps users display many different dimensions of clinical and molecular data simultaneously,’ Lenburg said. ‘For example, for a given set of tumor biopsies, it is possible to see which regions of the genome are abnormal, how much of every gene is being expressed, how active various signaling pathways are–all organized by, say, how well each patient responded to a particular drug. As a result, the process of identifying possible connections is really easy.’

The Cancer Genomics Browser represents data as ‘heatmaps,’ in which colors represent the values of key variables. Genomic and clinical data are displayed side by side, and researchers can group and sort the data on the basis of any feature of interest, such as age, gender, response to therapy, estrogen-receptor status of breast cancers, and so on. Because humans excel at visual pattern recognition, correlations in the data tend to jump out as the user manipulates the browser display.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics