UC Davis researchers have identified the molecular interactions that allow capsaicin to activate the body’s primary receptor for sensing heat and pain, paving the way for the design of more selective and effective drugs to relieve pain. Their study appeared online June 8 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

UC Davis researchers have identified the molecular interactions that allow capsaicin to activate the body’s primary receptor for sensing heat and pain, paving the way for the design of more selective and effective drugs to relieve pain. Their study appeared online June 8 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Capsaicin is the ingredient that makes chili peppers spicy and hot. The same pathway in the body that responds to spicy food is also activated after injury or when the immune system mounts an inflammatory response to bacteria, viruses, or in the case of autoimmune disease, the body’s own tissues.

“While we have known that capsaicin binds to the TRPV1 receptor with exquisite potency and selectivity, we were missing important atomic-level details about exactly how the capsaicin molecule interacts with TRPV1, one of the body’s primary receptors for sensing pain and heat,” said Jie Zheng, professor of physiology and membrane biology at UC Davis and senior author on the paper.

Using computer models based on atomic force fields and existing low resolution 3-D reconstructions of the TRPV1-capsaicin complex, the researchers identified several structural areas that enable capsaicin to strongly bind to the TRPV1 receptor.

“Computational biology methods are becoming very powerful tools for predicting and ultimately validating the high-resolution structure of important biological proteins and ligands, such as capsaicin and TRPV1, when they interact,” said Vladimir Yarov-Yarovoy, assistant professor of physiology and membrane biology at UC Davis and co-author on the study. “These tools are especially useful when the interactions are small and transient, and cannot be captured easily with high-enough resolution using traditional experimental approaches.”

Fan Yang, postdoctoral fellow in the Zheng lab at UC Davis and first author on the paper, agrees.

“The electron density observed in the cryo electron microscopy structure of the TRPV1-capsaicin complex is much smaller in size compared to the chemical structure of capsaicin,” Yang said. “With computational docking, we were able to detail the atomic interactions between capsaicin and the TRPV1 channel and later validate the molecular architecture using other experimental approaches.”

The new structural information may serve to guide the drug-design process, the researchers said.

“Just as we can ‘get used to’ a spicy dish by the end of the meal, we believe that there are ways to develop highly specific molecules that make TRPV1 less sensitive to painful stimuli,” Zheng said.

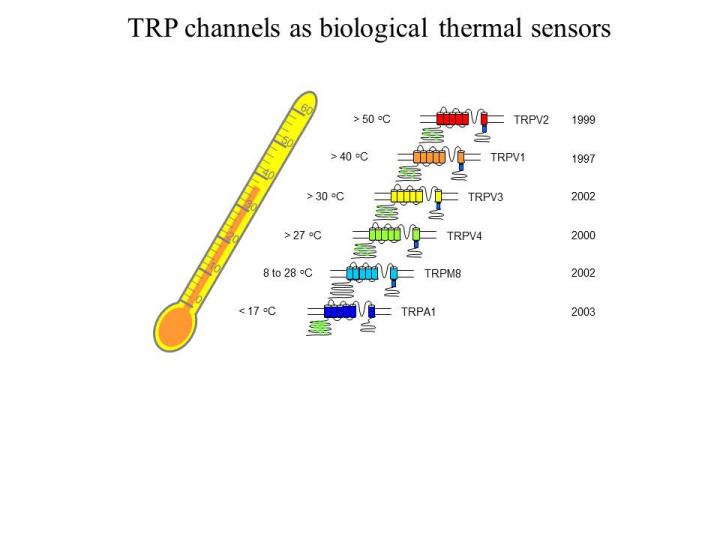

The research also explains why capsaicin does not activate the body’s other channels for sensing temperature, and why the TRPV1 receptor in many other species is not activated by capsaicin. For example, birds are missing two key interaction sites, which explains why birds are insensitive to the spiciness of chili peppers.

“It is thought that the presence of capsaicin is an evolutional advantage for plants, protecting them from species that would eat the leaves while allowing birds to ingest the peppers to spread the seed,” Zheng said.

The researchers also found that sweet peppers contain a compound called capsiate, which is almost identical to capsaicin in spicy peppers but differs at one key interaction site.

“The difference is sufficient to make the sweet pepper compound bind to TRPV1 very poorly, which is probably part of the reason why it does not taste spicy,” Zheng said. “On the Scoville pungency scale, capsaicin is 16 million, and capsiate is only 16,000.”

Source: University of California – Davis Health System

Filed Under: Drug Discovery