Image courtesy of Unsplash user Testalize

In the late 1990s and early to mid 2000s, the consensus in case law and within United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) guidelines was that determination of an antigen was sufficient to allow a patentee to claim the genus of antibodies that bound the antigen. This rationale was based on the idea that once the antigen was determined, it was relatively trivial to obtain the antibodies that bound such an antigen.

Subsequently, however, a number of court opinions have redefined what is considered adequate disclosure to support broad antibody claims in the first paragraph of 35 U.S. Code 112.

The following section provides a high-level review of such opinions to support the analysis in the subsequent section. These decisions were made by the U.S. Federal Circuit, the court specifically tasked with dealing with IP issues and second only to the U.S. Supreme Court on such matters.

Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc. versus Abbott Laboratories (Federal Circuit 2010)

Centocor created chimeric antibodies that bind to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and filed a number of patents, including U.S. Patent No. 7,070,775 (“the ’775 patent”). Subsequently, Abbott filed a fully human antibody that would bind to TNF and marketed it as the drug, Humira. Centocor filed claims to “isolated recombinant anti-TNF antibody or antigen-binding fragment thereof. . .comprising a human constant region. . .” based on their earlier filing and argued that Abbott was infringing their patent.

Claim 1 of Centocor’s patent was:

1. An isolated recombinant anti-TNF-α antibody or antigen-binding fragment thereof, said antibody or antigen-binding fragment comprising a human constant region, wherein said antibody or antigen binding fragment (i) competitively inhibits binding of A2 (ATCC Accession No. PTA-7045) to human TNF-α, and (ii) binds to a neutralizing epitope of human TNF-α in vivo with an affinity of at least 1×108 liter/mole, measured as an association constant (Ka), as determined by Scatchard analysis.

Abbott argued that the patent was invalid for lack of written description under 35 U.S.C. S 112, ¶ 1:

The written description requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112, ¶ 1 provides, in pertinent part, that: The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.

Centocor cited earlier case law, Noelle versus Lederman, 355 F.3d 1343 (Federal Circuit 2004):

the ’775 patent “does much more than what the [USPTO written description] Guidelines and Noelle suggest,” in that it not only describes the antibodies by their binding affinity for TNF-α, but further describes the antibodies by specifying that they competitively inhibit binding of the A2 mouse antibody to TNF-α.

The court found that Centocor’s later claims were not supported by the earlier application filed. Further, with regard to the PTO’s Guidelines and Noelle, the court specifically stated:

[Centocor’s premise] is based on an unduly broad characterization of the guidelines and our precedent.

The current PTO written description guidelines include an antibody example. Referencing only an immunology text published in 1976, the PTO guidelines indicate that a functional claim reciting “an isolated antibody capable of binding to [protein] X” is adequately described where the specification fully characterizes protein X – even if there are no working or detailed prophetic examples of actual antibodies that bind to protein X. U.S.P.T.O., Written Description Training Materials, Revision 1 March 25, 2008 at 45–46 (available at https://www.uspto.gov/web/menu/written.pdf).

In Noelle, we discussed the PTO’s antibody example. 355 F.3d at 1349. This broad claim covered antibodies that bind CD40CR from any species, however, the specification did not describe any antibodies to human CD40CR or CD40CR from any other species, nor did it describe any CD40CR protein from any species except mouse. We concluded that Noelle’s specification did not provide adequate written description for such broad claims. While our precedent suggests that written description for certain antibody claims can be satisfied by disclosing a well-characterized antigen, that reasoning applies to disclosure of newly characterized antigens where creation of the claimed antibodies is routine.

AbbVie Deutschland GMBH & Co. v. Janssen Biotech, Inc. & Centocor (Federal Circuit 2013)

AbbVie owned U.S. Patents 6,914,128 and 7,504,485, directed to fully human antibodies that bind to and neutralize the activity of human interleukin 12 (“IL-12”), which can cause psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis.

AbbVie developed its IL-12 antibodies using phage display, which involved creating a large library and screening for fragments that encoded an antibody fragment with IL-12 binding affinity. AbbVie identified a lead through screening that it named “Joe-9”, which had the ability to bind to and neutralize the activity of IL-12, albeit with low affinity. In order to improve IL-12 affinity, AbbVie introduced mutations to the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of Joe-9 and then used site-directed mutagenesis to alter individual amino acids at selected positions and generated additional antibodies, among which an antibody that it named “J695” showed a significant increase in IL-12 binding and neutralizing activity.

The ’128 and ’485 patents described the amino acid sequence of about 300 antibodies having a range of IL-12 binding affinities. Because the IL-12 antibodies described in the patents were all derived from the same parent, Joe-9, they all had VH3 type heavy chains and Lambda type light chains. The described antibodies shared a 90% or more amino acid sequence similarity in the variable regions. And over 200 of those antibodies were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and thus differ by only one amino acid and share a 99.5% sequence similarity in the variable regions. The application stated that “other VH3 family members could also be used to generate antibodies that bind to human IL-12” or that “other Vλ1 [Lambda 1] family members may also be used to generate antibodies that bind to human IL-12,” but did not describe any IL-12 antibody having heavy chains outside of the VH3 family or light chains outside of the Lambda family.

The claims of the ’128 and ’485 patents at issue defined the claimed antibodies by their function, i.e., IL-12 binding and neutralizing characteristics, rather than by structure. Claim 29 of the ’128 patent is representative and reads as follows:

29. A neutralizing isolated human antibody, or antigen-binding portion thereof that binds to human IL-12 and disassociates from human IL-12 with a koff rate constant of 1×10-2 s-1 or less, as determined by surface plasmon resonance.

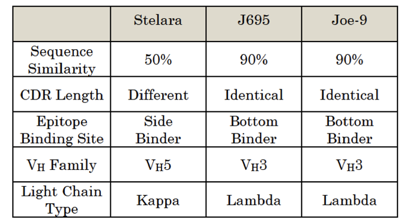

Janssen/Centocor developed its human IL-12 neutralizing antibody drug marketed under the brand name Stelara using the transgenic mice technology, which involved mice that were genetically modified with human antibody genes and capable of producing human antibodies when exposed to an antigen such as IL-12. Stelara had VH5 type heavy chains, not VH3, and Kappa type light chains, not Lambda, and about 50% sequence similarity in the variable regions as compared to the Joe-9 antibodies described in the ’128 and ’485 patents.

Janssen/Centocor raised four invalidity defenses on the bases of written description, enablement, obviousness, and anticipation by prior invention. To support its invalidity challenges under § 112, Janssen/Centocor presented evidence seeking to establish that the antibodies described in AbbVie’s patents were not representative of other members of the functionally claimed genus, which included Stelara, but were limited to a family of closely related, structurally similar antibodies that are all derived from Joe-9. Janssen/Centocor presented expert testimony that the antibodies described in the patents were structurally similar, but that they differed from Stelara in many respects, set out below:

AbbVie argued that each of the asserted claims were limited to a small genus of antibodies and that its patents described a representative number of antibodies commensurate with the scope of the claims. AbbVie maintained that the disclosed antibodies reflect the variation of the entire genus because they cover the full range of the claimed feature, the koff rate. AbbVie also asserted that it disclosed the amino acid sequence of all known species covered by the claims except for Stelara and that its patents were not required to provide individual written description of an infringing product. AbbVie argued that Janssen/Centocor incorrectly sought to distinguish Stelara on the basis of unclaimed structural features that are legally irrelevant and have no correlation to the claimed koff rate. AbbVie maintained that even if the structural variations were relevant at all, AbbVie’s patents disclosed a variety of amino acid sequences of the CDRs of its antibodies.

The court sided with Janssen/Centocor that substantial evidence supported that the claims were invalid for lack of an adequate written description. The court stated:

when a patent claims a genus using functional language to define a desired result, “the specification must demonstrate that the applicant has made a generic invention that achieves the claimed result and do so by showing that the applicant has invented species sufficient to support a claim to the functionally-defined genus.” The court has held that “a sufficient description of a genus . . . requires the disclosure of either a representative number of species falling within the scope of the genus or structural features common to the members of the genus so that one of skill in the art can ‘visualize or recognize’ the members of the genus.”

***

Although the described antibodies have different amino acid sequences at the CDRs, they share 90% or more sequence similarity in the variable regions and over 200 of those antibodies differ by only one amino acid. Although the number of the described species appears high quantitatively, the described species are all of the similar type and do not qualitatively represent other types of antibodies encompassed by the genus.

The patents must at least describe some species representative of antibodies that are structurally similar to Stelara. On review of the record, there is no evidence to show any described antibody to be structurally similar to, and thus representative of, Stelara. There is also no evidence to show whether one of skill in the art could make predictable changes to the described antibodies to arrive at other types of antibodies such as Stelara.

The court went on to conclude:

Functionally defined genus claims can be inherently vulnerable to invalidity challenge for lack of written description support, especially in technology fields that are highly unpredictable, where it is difficult to establish a correlation between structure and function for the whole genus or to predict what would be covered by the functionally claimed genus.

Amgen Inc. versus Sanofi, Aventisub, LLC (Federal Circuit 2017)

The patents at issue related to antibodies for reducing “bad” cholesterol. The antibodies were PCSK9 inhibitors. Amgen’s research resulted in the drug Repatha, which uses a monoclonal antibody that targets PCSK9 to prevent it from destroying proteins that reduce LDL-R. Two patents issued covering Amgen’s monoclonal antibodies and the claims were directed to an entire genus of antibodies that bind to specific amino acid residues.

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDL[-]R.

In developing the drug, Amgen screened more than 3,000 human monoclonal antibodies and narrowed the number to approximately 85. In addition, Amgen provided three dimensional structures of two of the antibodies along with a number of competing antibodies.

Sanofi’s research in the PCSK9 area resulted in the development of Praluent, a monoclonal antibody that targets PCSK9 also. The USPTO issued a patent to Praluent, which claimed the drug by its amino acid sequence. Amgen sued Sanofi, claiming patent infringement.

In reviewing the district court’s decision, the Federal Circuit made a number of determinations and remanded the case back to the district court.

The court stated that post-priority-date evidence proffered to show that the patents in suit did not provide adequate written description is allowed.

It further reiterated that 35 U.S.C. § 112 requires a written description of the invention without exception, stating that the “newly characterized antigen” test as described in Centocor (2010):

flouts basic legal principles of the written description requirement. Section 112 requires a “written description of the invention.” But this test allows patentees to claim antibodies by describing something that is not the invention, i.e., the antigen. The “newly characterized antigen” test thus contradicts the statutory “quid pro quo” of the patent system where “one describes an invention, and, if the law’s other requirements are met, one obtains a patent.”

Currently, it is advisable for life science innovators to consider the impacts of Centocor, Abbvie, and Amgen when planning and developing their patent portfolios. In particular, sufficient consideration should be given regarding the inclusion of sufficient support (e.g, structure, properties, characteristics, a number of working examples) for protein-based claims to fully illustrate the inventor(s) were in possession of the full scope of the claims desired.

Troy Groetken is a shareholder, board member and executive committee member with McAndrews. He has approximately 25 years of legal experience in the intellectual property field and more than 25 years of technical experience in the pharmaceutical, biotechnological and chemical fields. He is recognized in the IAM Patent 1000: The World’s Leading Patent Professionals, and has been cited in the Best Lawyers in America list since 2012.

Troy Groetken is a shareholder, board member and executive committee member with McAndrews. He has approximately 25 years of legal experience in the intellectual property field and more than 25 years of technical experience in the pharmaceutical, biotechnological and chemical fields. He is recognized in the IAM Patent 1000: The World’s Leading Patent Professionals, and has been cited in the Best Lawyers in America list since 2012.

Filed Under: Drug Discovery, Drug Discovery and Development

Tell Us What You Think!

You must be logged in to post a comment.