In this Nov. 13, 2017 file photo, Brian Madeux, starts to receive the first human gene editing therapy for Hunter syndrome, as his girlfriend Marcie Humphrey, left, applauds at the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in Oakland, Calif. At right is nurse practitioner Jacqueline Madden. Gene editing aims to permanently change someone’s DNA to try to cure a disease. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

A second patient has been treated in a historic gene editing study in California, and no major side effects or safety issues have emerged from the first man’s treatment nearly three months ago, doctors revealed Tuesday.

Gene editing is a more precise way to do gene therapy, and aims to permanently change someone’s DNA to try to cure a disease.

In November, 44-year-old Brian Madeux became the first person to have gene editing inside the body for a metabolic disease called Hunter syndrome that’s caused by a bad gene. Through an IV, he received many copies of a corrective gene and a genetic tool to put it in a precise spot in his DNA.

“He’s doing well and we were approved to go ahead with the second patient who also is doing well,” said Dr. Paul Harmatz of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, who treated both men for the same disease.

At a medical conference in San Diego, Harmatz reported safety results for the first six weeks after Madeux’s treatment. Sangamo Therapeutics, the company that makes the gene editing tool called zinc finger nucleases, is testing them for two metabolic diseases and hemophilia, a bleeding disorder.

The company said more safety information and initial results on effectiveness should come by mid-year.

Madeux had dizziness, cold sweats and weakness four days after the treatment but they went away on their own in a day, Harmatz said. Madeux also had a severe cough and a partially collapsed lung, but these were deemed unrelated to the gene therapy because he had had similar problems previously.

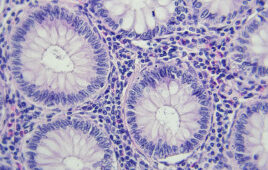

Importantly, there were no signs of harm to his liver.

“That’s the big worry” because changes in the liver might mean the immune system was fighting the treatment and possibly undermining its effectiveness, Harmatz said.

The liver results were welcome news after some other recent reports caused alarm. A prominent gene therapy scientist, Dr. James Wilson of the University of Pennsylvania, published two studies reporting liver and other serious problems in monkeys and piglets that were given experimental gene therapies. Several had to be euthanized.

The animal studies tested very high intravenous doses of a therapy that used a certain virus to carry the gene into cells. Relatives of this virus are widely used in human gene therapies, but Wilson said he does not believe that the results in animals have any bearing on use of lower doses, different types of the virus, or therapies given in different ways such as a shot.

The results might mean it will be harder to develop gene therapies for some neuro-muscular disorders — higher doses in the animal studies were thought necessary to get the therapy into the brain and throughout muscles.

The Sangamo study that Madeux is in used much lower doses of a different type of the virus.

Wilson said it was important to the field that any safety concerns be published quickly. He helped lead a very early gene therapy experiment that killed a teen in 1999, putting some other studies on hold for years.

An editorial in the journal Human Gene Therapy, which published one of Wilson’s animal studies, said gene therapy experiments should not stop because that might deprive patients of potentially life-saving treatments.

In the last year, the first gene therapies were approved in the United States to treat cancer and an inherited form of blindness.

Filed Under: Genomics/Proteomics